On March 22, 2019, Daesha Devón Harris, Luis Jimenez Inoa, and Kambui Olujimi sat down with Dayton Director Ian Berry and Mellon Collections Curator Rebecca McNamara to look through a recently acquired collection of vernacular photographs.

Daesha Devón Harris

I like these pictures of people enjoying the outdoors or flora and fauna in the photo with people.

Luis Jimenez Inoa

I am particularly drawn to photos that disrupt stereotypes. Black people don’t go near water, right? Black folks aren’t typically captured having fun, or …

DDH

Or going outdoors.

LJI

I don’t know if you ever took a picture in front of a car that wasn’t yours?

Kambui Olujimi

I have—ages five to eleven.

LJI

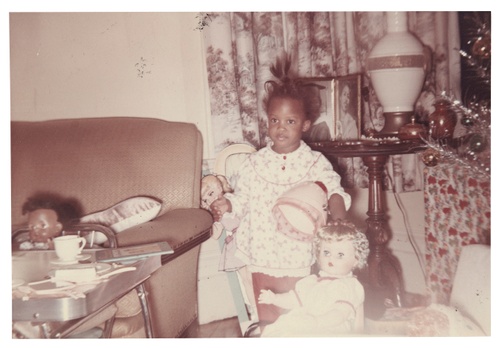

I’m curious about things that show possession, things that show wealth, or what it means for people who have historically and generationally been owned to begin to own things, and how that might be caught in photos. You see these car pictures, toy pictures …

KO

As a little kid, you do the same thing. You’re like, “This is mine.”

DDH

Yes!

KO

This is mine; let’s take a picture with it.

DDH

I feel it’s less about possession, and more, this is the fruit of my labor. This is evidence of my work and pride. Of course, we all have been in front of those fancy cars, where it’s just about the car. But look at this adorable couple in front of a home. I love these photos. Homeownership is still such a fight.

I particularly love this one of the woman in the garden with her onions or potatoes and tomatoes. She’s so proud of the garden. I’m a gardener, so I know how that feels. That’s been in my family for as long as I can remember. Both sides, gardening. My cousins think it’s hysterical. It’s as if it’s gone out of our family memory from living in the city for so long. And so, when they come over, they’re like, “Oh, Daesha, you’re so weird.” But this is what our grandmother did to feed the family. We lose sight of the history that’s not so far back at all. These are the kinds of activities that you never see popularized.

KO

The beach pictures stand out for me because elsewhere, you don’t see black intimacy much. Moments where you’re at the beach and it’s your body, but it’s not charged in the way that the black body often gets framed in America. It’s sensual, it’s jokey, it’s goofy. The continuum, the spectrum, is there. Like, I’m in the water, but I don’t want to get wet. I’m literally climbing on you, even though I’m grown. From this one, which is like, I worked all summer for us to make this fantasy of Virginia Beach, to okay, wait, wait, hold on, get it, I have, like, my leg, wait, put your leg, like, here … There’s an absurdity here. That’s the space of the beach—everyone is basically in their underwear, playing, laughing, doing all the things that the barrier of clothing holds down.

LJI

Those pictures are similar to these, where somebody is holding somebody else. There is typically a little bit more intimacy between people in the beach pictures. Not as often men with men. And even in the pictures of home, when you find people in the living room, and they’re holding each other, not often is a black male touching another black male. You might find these in army photos, but images of intimacy between black men and their children or family members are scarce.

DDH

I also wonder who is taking the photo. Because in my family, it was my uncle who was the photographer or my grandfather who was the photographer and always had the camera.

LJI

They’re there, but not in the picture. In my family, it was my father who was the photographer, and so he’s not in a lot

of pictures. And when I see him in a picture, it’s special. And the same with my family, I’m the one that ends up taking the pictures.

KO

Unfortunately, I think part of it is homophobia, and the homophobia of the time, and notions of upstandingness. Status quo plays into a lot of these, where you don’t want to record anything that is not on par. I think about this a lot. I want my nephews to see that I’m loved, and how I’m loved by my brothers. Some of it is awkward. I think we’ve seen the subtle awkwardness of the everyday in many of these pictures.

LJI

There’s something about finding the holy in the ordinary—you know, the things that make something special. And how often are those captured from day to day?

DDH

This whole collection in general has never been our public narrative, which is why it’s so lovely. All these different aspects that we’re still resisting and fighting against. Stereotypical images of us are so normal. I’m so happy that this museum has alternative imagery as references for the students.

LJI

It certainly made me think about what it means to have a subject, in terms of what you’re photographing … But these photos are meant for the family. Would it be too cheesy to say, “now I am family”? Or am I intruding on a private moment that was never really meant for my eyes? For these particular photos, this was meant to send to Grandma, meant for Grandma’s eyes. This was meant for her to be able to look back, not meant for Luis in 2019 to sift through. What does it mean for family photos that capture rather intimate moments to be out for public consumption, for the public gaze?

KO

I think about how time erodes privacy. You’re a kid, and you have this secret, and you fold it up, and you put it away. As time goes on, whether it’s a tomb in ancient Egypt or the attic with all your diaries, there’s a way in which time eats away at the shell of our privacy. And the same thing as things move. In Brooklyn, when I’m looking at found photographs in flea markets, a lot of times they’re estates. You die, and your forty thousand heartfelt photographs are now junk. It’s a shift of value, and that shift cracks open that shell of privacy.

DDH

Isn’t that the history of art, though? We are constantly reinterpreting images and visuals and mementos from the past.