Erica Wojcik

Assistant Professor of Psychology

Skidmore College

What does the world look, sound, and feel like to a newborn infant who does not yet have the knowledge to make sense of it?

Psychologist Alison Gopnik describes human development as the transformation from a lantern into a spotlight. As lanterns, infants shine their attentional light everywhere. They do not know where to look to find meaning, and so they attend to and process many things around them. As adults, without even realizing it, we focus our attention like a spotlight, exclusively on the information that matters (or that seems to matter based on our past experiences). For example, while we are all born able to hear the difference between a d sound made with your tongue at your teeth versus at the roof of your mouth (try it!), English learners quickly stop noticing this acoustic difference because it doesn’t matter in English. (It does matter in other languages, such as Hindi.) After living in an English-speaking environment for only twelve months, babies just hear a d, regardless of how someone moves their tongue to produce it, unconsciously shining their developing language spotlight only on the parts of the speech stream that affect their own world.

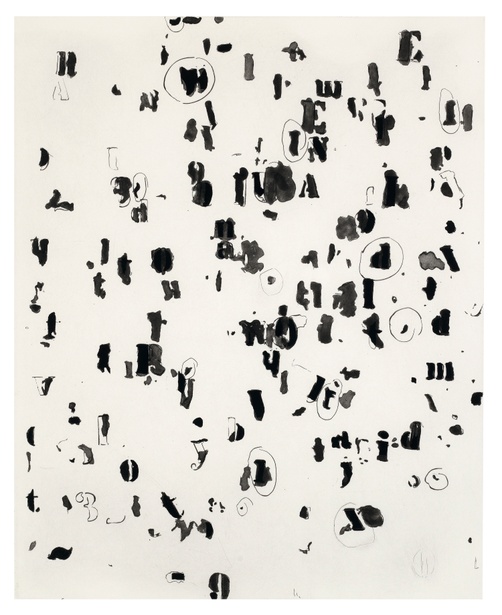

Glenn Ligon’s Draft (2010) is different from much of his other text-based works, which involve legible phrases. While the phrases in works like Untitled (I am an invisible man) (1991) are often degraded or smudged, we are able to see the words clearly enough to read them. In Draft, we instead see letters and partial letters, jumbled and overlapping across the paper. As I tried to find patterns in the letters—do the circled marks spell anything? Does a word pop out if I stare at it for a long time, like a magic-eye drawing?—I realized that Draft was turning me back into a lantern. When I view Ligon’s other works, I can’t help but shine a spotlight on the printed sentences to read their meanings, initially ignoring the textures of the print itself. In Draft, there is no information to shine a spotlight on. After first trying to find pattern and meaning, I felt my perceptual aperture widening, my constructed boundaries softening, and I was able to let my eyes wander, from darker shapes to lighter ones, from straight edges to curved ones.

While our adult spotlight makes us more efficient at processing the world—how exhausting would it be to notice every sensation around us all the time?—it comes at a cost. Infants may not be able to understand the meaning of a sentence or the message behind a gesture, but they may, in a way, perceive more of the world than we do. How they view and interpret the world is not yet constrained by their experiences. By printing letter-like but illegible symbols in Draft, Ligon, perhaps, asks us to let go of our spotlight shortcuts and spend time with the textures and shapes of written language. In this way, Ligon unburdens us of our past and the biases that we’ve built up to become more efficient, encouraging us to see more.